5 great (non-documentary) movies for urbanists

1. Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927), dir. F.W. Murnau

Murnau’s masterpiece Sunrise might be the great anti-urban film. The German Expressionist director Murnau moved to Hollywood after directing his other masterpiece, Nosferatu, putting together three silent films and a documentary before his death in 1931 at the age of 43.

Steeped in the cinematic language of German cinema like The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, Murnau’s European sensibility fit uncomfortably in the U.S. Sunrise is about two farmers (succinctly referred to as The Man and The Wife). The Man toils away in the fields until, seduced by the wickedly wily Woman from the City, he contemplates murdering The Wife by dumping her into a lake. Stricken with regret in the middle of the act, he rows them both back to shore, but pursues her into town where she goes to escape her husband.

The Man’s short sojourn in urban America will pique the interest of anyone looking for early evidence of America’s great white suburban retreat. In this film, it’s portrayed as both grotesque and overwhelming, with coteries of anonymous extras boxing in the farmers at every turn, a place where cars pose a constant danger.

The thick lines it drew between the hardworking but depressingly sedate pastoral American lifestyle of the nineteenth century and the exhilarating but confusing (and morally questionable) urban 20th century are still with us.

2. Zabriskie Point (1970), dir. Michaelangelo Antonioni

In Antonioni’s more widely lauded 1960 film L’Avventura, the main characters’ unquestioned ability to simply walk in and out of public and private space becomes a class marker – no one ever tells Monica Vitti to go away. Neither crumbling rural Italy nor wide-open Modernist cityscapes warrant much comment from the protagonists. That cultivated alienation is part of the point, alongside the permeability of their surroundings.

Like Sunrise was for Murnau, Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point was his first film in America; like Murnau, Antonioni was fascinated with the texture of American architecture and transportation, from trashy, billboard-filled freeways to hippie communes to the private perches of the well-off; from trucks driven down lonesome highways to private planes.

The daffy and barely-sketched plot concerns two rebellious Americans in their early twenties, Mark and Daria. Mark is a self-styled Marxist revolutionary who steals and isn’t averse to violence; Daria is a dutiful functionary in a real estate development firm. Meeting and unmeeting, the two go on parallel impromptu road trips, Daria to her boss’s mansion and Mark fleeing Los Angeles. Noticeably, the movie begins with a racially diverse crowd discussing politics, but later, when Mark and Daria encounter a hippie orgy in the desert, everyone’s white. Meanwhile, Daria’s boss Lee listens on the radio as a radio announcer casually discusses a slum destruction project.

Eventually, Mark is killed and Daria blows up her boss’s house. The notoriously abstruse Zabriskie Point is ultimately about American community: who it excludes and includes; the meeting points of rich and poor (mostly at work); the places we reserve for ourselves (like the desert park that gave the film its name) and the places where the public is excluded, on pain of death. The varying difficulty with which its characters traverse their landscape is ultimately what distinguishes them from each other.

3. Chinatown (1974), dir. Roman Polanski

Hear me out. A lot of film noir from the ‘40s and ‘50s portrayed dishonest cops, femmes fatales, and hard-boiled detectives. The focal points for Chinatown, on the other hand? All those, plus land ownership and infrastructure. Sure, there’s the incestuous relationship between Faye Dunaway and her dad. Sure, there’s the Jack Nicholson’s traditional sneer. But the linchpin of the film is the difficult (and still unanswered) question of how to supply enough water for everyone in Los Angeles.

Nicholson’s Jake Gittes solves the murder of Hollis Mulwray by paying an urbanist’s attention to resource scarcity, getting knifed in the nose by a Water Department employee (surely the only time in the history of cinema that that’s happened). He gathers property ownership data (in the form of a trip to the city’s public records department), drives tirelessly from L.A. to the northwest valley and back, over and over, and foils John Huston’s attempt to muscle annex nearby farmland. In the early 21st century, Jake Gittes would’ve made a great hire for CityLab or Streetsblog.

4. Brazil (1985), dir. Terry Gilliam

Notable for its relentless satire of top-down urban design under a dictatorship, Terry Gilliam’s nightmare is probably Jane Jacobs’s, too. Nonstop billboards on the side of a road featuring a beaming, 1950s-style family insist that “We’re all in it together!”, but the sign is belied by the desolate wasteland the billboards conceal.

If you haven’t seen it, Brazil is a satire that takes place in a viciously oppressive British state where everyone toils away either as a minor bureaucrat or on massive industrial estates. The architecture tends more toward Albert Speer than Christopher Wren, with convoluted pneumatic pipes and ductwork everywhere. We never find out the name of the city where the hero Sam Lowry lives, but much of it looks an awful lot like the Brutalist apartment buildings near the Barbican in London. There’s public transit, sure, but besides a few kids playing in the mud of a parking garage, no neighborhoods to speak of.

Anyway, the plot is mostly a MacGuffin that provides an inroad for the audience into the battle between the oppressive government and a vaguely-defined cadre of “terrorists.” In terms of its portrayal of city life, though, Brazil looks like what might happen if everywhere was planned out by an urban renewal enthusiast, with vacant streets, poverty pushed out of town into bleak suburban housing blocks that create more problems than they solve, and overlarge plazas that, once built, don’t do much but scare the shit out of everyone walking through them. Much of the film’s profound sense of alienation comes from the terrifying lack of non-consumerist, non-bureaucratized public space.

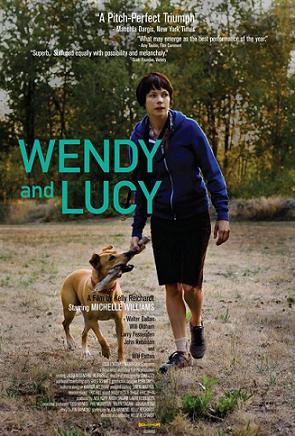

5. Wendy and Lucy (2008), dir. Kelly Reichardt

Reichardt’s small but distinctive body of work explicitly addresses the American landscape: its rhythms, disruptions, and how we get around within it. Meek’s Cutoff, while definitely not for everyone, treated one family’s westward expansion as a personal and moral disaster; Night Moves was itself named after the boat that a cell of Oregon environmentalists use to blow up a dam in the movie.

Reichardt’s small but distinctive body of work explicitly addresses the American landscape: its rhythms, disruptions, and how we get around within it. Meek’s Cutoff, while definitely not for everyone, treated one family’s westward expansion as a personal and moral disaster; Night Moves was itself named after the boat that a cell of Oregon environmentalists use to blow up a dam in the movie.

Wendy and Lucy mounts a subtle but devastating critique of car-based American society. A homeless twenty-year-old free spirit living in her car with her dog, trying not to spend her last few hundred dollars, Wendy is on her way to a job in Alaska when her Honda breaks down in Oregon. Having to parcel out her money, she finds herself arrested for shoplifting, which strands her dog; she has to live in a parking lot, where a forgiving security guard whose job is to kick her out provides her only human company; she ends up in hock to an unethical mechanic. In the meantime, she can’t get around the town she’s in except by bus, and even that involves long walks.

Ultimately, Wendy has to hitch a ride on a freight train, having lost everything. In the devastating final shots, we see on Michelle Williams’s face the very real suffering imposed by being situated in a society that presumes vehicle ownership as the cost of participation. Without food, money, or any social support, even the small measure of hope she begins the movie with has disappeared with her car.

Related Posts

Category: Miscellaneous