Black pedestrians must wait 32% longer than whites at U.S. crosswalks

Black pedestrians may be experiencing discrimination at crosswalks, according to a new study. “Racial bias in driver yielding behavior at crosswalks” by researchers Tara Goddard, Kimberly Barsamian Kahn and Arlie Adkins found that black participants were twice as likely as white participants to be passed by two-plus cars. Additionally, the found that black participants experienced a 32 percent longer wait before drivers yielded.

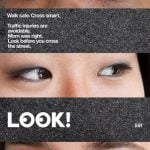

Black pedestrians have to wait 32% longer than white counterparts before drivers at crosswalks will yield. Image from stimpsonjake.

While psychological and social identity factors have been studied before, revealing drivers’ behavior towards pedestrians, there haven’t been any studies that investigate drivers’ potential racial bias’ impact on yielding — or not yielding — to pedestrians. The study has significant implications for health and safety: Drivers’ yielding behavior could lead to “disparate pedestrian crossing experiences based on race and potentially contribute to disproportionate safety outcomes for minorities.” Crosswalks are arguably the most vulnerable spot for pedestrians.

For the controlled experiment, the researchers used an “unsignalized midblock marked crosswalk in downtown Portland, Oregon” and employed on six trained male participants, three white and three black, to simulate an individual pedestrian crossing while trained observers tallied the number of cars that passed, as well as the time until the driver yielded.

The results, which encompassed 88 pedestrian trials and 173 driver-subjects, showed that black pedestrians were passed by twice as many cars and experienced wait times that were 32 percent longer than white pedestrians’ wait times. As the researchers write, “[M]inority pedestrians experience discriminatory treatment by drivers at crosswalks.” Simply put, more drivers passed by and did not stop for black pedestrians than for white pedestrians who were waiting at the crosswalk to cross the street.

The researchers couldn’t form conclusions about the source of the drivers’ racial bias, since the experiment was a “naturalistic field experiment” and didn’t involve driver interviews or other methods. As the researchers point out, “It is possible that drivers were consciously, overtly, and explicitly racially biased in their stopping decisions, deliberately deciding to not stop for black pedestrians.” But the researchers did suggest that certain attitudes come to the fore when driving in certain situations: “Implicit attitudes are more predictive of behavior when situations necessitate quick decisionmaking, distractions are present, and anonymity is increased… as exists when driving on a busy street.”

“Although it may seem small,” conclude the researchers, “the observed disparity may contribute to the myriad small inconveniences and indignities faced by minorities known as microaggressions. Our finding of racial bias consistent with microaggressions has implications for transportation officials working to increase participation in active transportation modes, as the additive effect of these repeated negative experiences while crossing may deter racial minorities from choosing to walk, and may contribute to the danger pedestrians face at street crossings.”

While the study proves this substantial bias, future studies will be necessary to determine the exact impact on pedestrian safety; another study might also investigate whether signage and other design features that make stopping seem more mandatory and, as the researchers say, “less discretionary.”

Related Posts

Category: Miscellaneous