Free parking fallacies: Infographic & report

[raw]

[/raw]

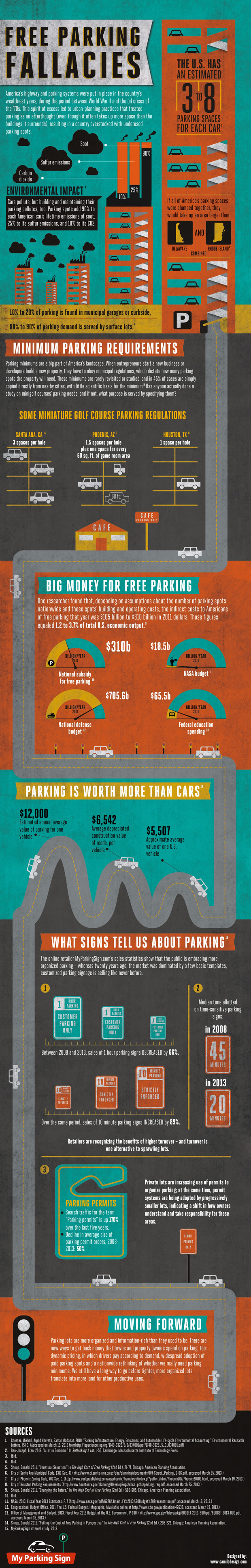

We at MyParkingSign are in a unique position to discern trends in how people are managing their parking lots. As part of an internal study, we looked into why some parking signs are selling more and others less, and why lot owners are looking for an increasingly diverse set of parking signs and permits – why the one-size-fits-all parking approach of twenty years ago no longer works. We were surprised to learn the extent to which the American landscape is changing, little by little, due to economic pressures – and also due to a more rigorous understanding of how parking impacts communities.

Infographic Report Podcast Descargar el infografía (Español)

Our key findings:

- The U.S. is oversupplied with free parking due to disorganized and sometimes ill-informed municipal planning practices, resulting in wasted land and resources.

- The market value of America’s parking is over $310 billion, but only a tiny percentage of its costs are ever recouped directly.

- As a response to the surprisingly high expense of providing free parking, many lot owners and lessees are beginning to adopt permit systems, allowing them to recover some of the costs of their parking.

- At the same time, the top-10-selling parking signs occupy a smaller and smaller portion of sales, indicating public demand for more varied organizational systems than before.

For more information, check out the infographic and report below. You can download the infographic here (JPEG, 5.3 MB), as well as the PDF (0.3 MB) or e-book (epub, 1.1 MB).

You can also click on the infographic for a larger version.

[raw]

[/raw]

[raw]

[/raw]

FREE PARKING FALLACIES – a MyParkingSign report

by Catesby Holmes with Conrad Lumm

We rely on parking for transportation, for shipping, for shopping, and for the odd back-lot basketball game or tailgate. We complain when we don’t have enough, but it makes housing and consumer prices more expensive, damages the environment, and can turn our surroundings into an eyesore. For this report, we spoke with parking experts Donald Shoup, Zhan Guo and Mark Chase to paint a picture of America’s parking scene today; we also reflect on what MyParkingSign’s sales statistics tell us about future trends.

A nation divided

Though the 2012 election season riled up America’s citizenry with various hot-button issues — abortion, gay marriage, healthcare — parking policy was not among them. Yet this subject is in some ways as politically controversial as any, pitting urban against suburban, carpoolers against solo drivers. The question any debate on parking begs is: does this country have too much parking? Or way too little?

The answer depends on whom you ask. For people living in America’s most densely populated cities (a diverse list whose top 50 include New York and San Francisco, as well as Sweetwater, FL and Huntington Park, CA), parking is a scarce resource. Getting a spot near home is iffy, and snagging one downtown a mere pipedream. For this four percent of America’s population, the surety that parking will cost time and money — and the alternative of using public transportation — influences where they go, when, and how they’ll get there.

“When deciding how to get into Manhattan, the likelihood of finding parking is by far my most important consideration,” says Brooklyn-based Eric Herman, a 30-year-old musician who, unlike many New Yorkers, owns a car. “During the week, it’s a no-brainer to take the subway, while on Sundays I prefer the car, because there’s actually parking in Manhattan then.”

Cleia Noia, of Sao Paulo, Brazil, notes that in her native city, where she drove to work daily, traffic and safety were her main considerations in choosing whether to drive. In New York, however, where she currently resides, Noia does not have a car — a circumstance she prefers. “Here, the difficulty in finding street parking and the expense of garages” are real deterrents. “For me, access to reliable, fast public transportation trumps access to a car most of the time.”

For the rest of the U.S., where public transportation is minimal and cars are generally a necessity, parking plays a different role in society. People drive everywhere, and they expect a place to put their vehicle when they get there. They’ve gotten their wish. It is estimated that there are at least three and possibly as many as eight parking spaces per car on the road:[1] one at home, another at work, and still more waiting for drivers when they visit the mall or eat at a restaurant.

While drivers appreciate the ease of parking, “The fact is that parking is oversupplied,” says Zhan Guo, a professor of urban planning at New York University who specializes in parking policy. “This is just common knowledge in the urban planning community.”

The oversupply is visibly evident in car-centric suburban areas, which are home to roughly 50 percent of the U.S. population[2] (some 150 million people). From shopping malls surrounded by double- and triple-digit acres of pavement to downtowns that have more surface lots than office buildings, America’s suburban periphery contains far more parking than it needs.

Much of this excess supply is due to municipal parking minimums, which require developers to include certain amount of parking with every new building. Guo’s research indicates that the U.S. parking supply would drop by up to 40 percent if minimums were eliminated, allowing parking to be supplied according to public demand, and priced using that demand as a guide. Yet despite ample evidence that parking is underpriced and oversupplied in the suburbs and exurbs, municipalities “don’t dare” try to charge drivers for parking, says Guo — it is too politically controversial.

Too much parking for too few cars

How much is too much? Eran Ben-Joseph, an M.I.T. professor whose 2012 book examines parking lot design, estimates that the United States has about 500 million surface spaces. That breaks down to 1.6 spaces for each person in the country, including such non-drivers as babies and the car-free. 80 to 90 percent of that demand is served by surface lots — that is, paved parking areas.

The other 10 to 20 percent of parking spaces is found in municipal garages and curbside (i.e., public street parking).[3] If all of America’s average 18-by-9-foot spot (162 square feet) parking spaces were clumped together, they would take up an area larger than Delaware and Rhode Island combined — with some estimates ranging nearly three times higher.

That’s a lot of pavement. In some cities, parking lots cover “more than a third of the land area,” writes Ben-Joseph, “becoming the most salient landscape feature of our built environment.” This phenomenon is often dubbed Pensacola Parking Syndrome , after the city that tore down buildings and built parking lots to attract people downtown to the point that the city center became a mere patchwork of empty lots, thus holding little enticement for visitors. It is a fate that befell many American downtowns in the mid-to-late 20th century.

While ample parking may attract drivers, surrounding buildings with sprawling lots have implications for the surrounding areas. Aesthetically, the implications are clear: miles of pavement lined with cars (or worse, absent cars) are not a stimulating sight. But large surface lots detract from an area’s general economic dynamism.

Shoppers or workers who drive to their destination, park their cars, walk through the lot to shop or work, and depart in their cars do all of that within the immediate environs of the mall or office. They do not pass nearby stores, restaurants, pubs, bookstores, or cafes that might draw them in were they to walk by.

The reasons behind America’s glut of parking are simple. First, Americans have a lot of cars: about one automobile for every two people, according to a 2012 report by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace ; these millions of vehicles are parked about 95 percent of the time, calculates Ben-Joseph — at home, at work, at the grocery store, at school, and the gym, and so forth. This is why the U.S. has upwards of three parking spots for every vehicle on the road.

Americans love their cars, which brings us to the second explanation for the United States’ plethora of parking: history. Detroit pioneered the car’s mass production; cars became an integral part of American culture, something associated with freedom, independence, and style. The car shaped much of the country’s built environment. When the United States’ population exploded in the second half of the 20th century, new suburbs were designed with the car in mind — its size, its speed, the great distances it could cover, and, yes, its parking needs. Cities and towns expanded outwards, less densely; roads became wider; parking lots proliferated, and expanded.

Since the 1950s, American demographic trends have changed as the population becomes increasingly urban. Today 32 percent of the Millennial generation lives in cities, a higher proportion than prior generations at the same age, according to a 2009 Pew Research Center report. A full 88 percent of Millennials told the Wall Street Journal they would prefer to live in an urban environment.[7]

“America had a love affair with the car,” says Mark Chase, a parking consultant at New York-based Nelson/Nygaard Consulting Associates. “Some are still in love, but for a lot of people it’s a bad relationship. And they’re looking for new affections.”

Young Americans in particular are just not enamored of cars the way their parents were. The New York Times recently reported that 46 percent of drivers aged 18 to 24 would choose Internet access over owning a car.

Trends in car use and ownership reinforce that disinterest. The percentage of people holding drivers’ licenses, for example, has been decreasing for a decade: less than half of potential drivers age 19 or younger have licenses, compared to two-thirds in 1998.[8] In the process, America has gone from #1 among car-owning countries to a middling number 25, just below oil-rich Bahrain and above Ireland, according to the Carnegie Report[9].

Finally, the kind of cars Americans drive has changed. Fading are the days of gas-guzzlers and tank-like SUVs. Instead, more and more people choose compact, fuel-efficient vehicles such as hybrids, Mini Coopers, or Vespa scooters. Ford and GM report high demand for new, more petite models[10] (the Focus and Sonic, respectively). And smaller cars means less space required for parking.

These changes in demography, car culture, and auto style have important implications about American identity. As author Richard Florida wrote in an Atlantic piece on why young people are rejecting cars, “The shift away from the car is part and parcel of a new way of life being embraced by young Americans, which places less emphasis on big cars or big houses as status symbols or life’s essentials.” Dubbing this phenomenon the “New Normal,” Florida writes that, “Whether it’s because they don’t want them, can’t afford them, or see them as a symbol of waste and environmental abuse, more and more people are ditching their cars and taking public transit or moving to more walkable neighborhoods where they can get by without them or by occasionally using a rental car or Zipcar.”[11]

Don’t tell drivers in New York or Boston, but this country has too much parking — at least in its rural and suburban areas. From Seattle-area office parks to Home Depots nationwide, research from the last decade reveals that some 50 percent of parking spaces in non-urban America go unused most of the year except during the two weeks of peak shopping during the winter holiday season.

Why are empty parking places a problem? Well, they’re unsightly, for one, and so much pavement is bad for the environment . But unused parking is also expensive. While differences in land value and other costs make it impossible to calculate precisely how much excess parking in the U.S. costs, Mark Delucchi of the University of California, Davis, estimated in 1991 that that annualized capital and operating cost of off-street parking fell between $79 billion and $226 billion each year, taking into account the land value, opportunity cost, transaction costs, and construction expenses involved in building and maintaining parking.

A decade later, Todd Litman of the Victoria Transport Policy Institute in British Columbia estimated that the “annualized economic value of all U.S. parking facilities” in 2000 was $500 billion (cited in his 2006 manual, Parking Management Best Practices).

Considering that roughly half (50%) of that parking goes empty 50 weeks (or 96%) of the year, and taking historic inflation into account, MyParkingSign calculates that excess parking could cost the country between $63 billion (the low end of Delucchi’s estimate) and $320 billion (Litman’s estimate) each year in today’s dollars. That’s up to $1,066 for each of the United States’ 300 million citizens, per year, including children and nondrivers.

These costs are largely passed on indirectly to consumers, notes Litman, “borne…through rents, taxes, and higher prices for retail goods.” Built-in parking expenses have particular impact in residential developments, where zoning usually requires a certain minimum of spaces. “Parking minimums are too high, so parking is created in oversupply, which increases housing costs,” says NYU’s parking expert Zhan Guo. “And that [additional cost] is subsidized by owners. If you get rid of minimum regulations, the market will supply parking at much lower level,” reducing the built-in cost for home buyers.

Put differently, “bundling the cost of parking spaces into the cost of dwelling units,” zoning regulations “shift the cost of parking a car into the cost of renting or owning a home — making cars more affordable but housing more expensive,” asserts Donald Shoup in The High Cost of Free Parking.

Take the example of developer who is constructing a building with 14 one-bedroom units in suburban Houston, TX. There, parking minimums require 1.333 spaces per one-bedroom apartment, meaning this building must have at least 19 parking spaces. Using Litman’s estimate of $432 as the annual cost of a single suburban surface-lot space, parking will add nearly $50 a month to each apartment’s rent. This price is paid even by such nondrivers as the elderly or those reliant on public transportation. In urban shopping centers, the annual expense of $2,083 per space is similarly built into product prices, highlighting the problem with spots that sit half empty during most of the year, except during the holiday season.

Typical Parking Facility Financial Costs

[raw]

| Type of facility | Land costs | Construction costs | O&M costs | Total cost | Daily cost | |

| Per acre | Per space | Per space | Annual, per space | Annual, per space | Per space | |

| Suburban, on-street | $50,000 | $200 | $2,000 | $200 | $408 | $1.36 |

| Suburban, surface, free land | $0 | $0 | $2,000 | $200 | $389 | $1.62 |

| Suburban, surface | $50,000 | $455 | $2,000 | $200 | $432 | $1.80 |

| Suburban, 2-level structure | $50,000 | $227 | $10,000 | $300 | $1,265 | $5.27 |

| Urban, on-street | $250,000 | $1,000 | $3,000 | $200 | $578 | $1.93 |

| Urban, surface | $250,000 | $2,083 | $3,000 | $300 | $780 | $3.25 |

| Urban, 3-level structure | $250,000 | $694 | $12,000 | $400 | $1,598 | $6.66 |

| Urban, underground | $250,000 | $0 | $20,000 | $400 | $2,288 | $9.53 |

| CBD, on-street | $2,000,000 | $8,000 | $3,000 | $300 | $1,338 | $4.46 |

| CBD, surface | $2,000,000 | $15,385 | $3,000 | $300 | $2,035 | $6.78 |

| CBD, 4-level structure | $2,000,000 | $3,846 | $15,000 | $400 | $2,179 | $7.26 |

| CBD, underground | $2,000,000 | $0 | $25,000 | $500 | $2,645 | $8.82 |

| O&M = operations and maintenance; CBD = central business district Direct financial parking facility costs under various conditions. Assumes 7% annual interest rate, amortized over 20 years. From Litman, Parking Management Best Practices, pg. 58. | ||||||

[/raw]

As a driver, you may think the biggest problem with parking is how expensive it is, or how scarce. But beyond those inconveniences, city planners and environmentalists see a graver set of issues. Sixty years of carving out space for America’s 250 million on-road vehicles has made parking – a broad category of infrastructure that includes street parking, garages, and parking lots – the “single biggest land use in any city,” says UCLA’s Donald Shoup. Think about that — all in all, parking takes up more space than buildings, parks, or industrial complexes. Any infrastructure of this magnitude will inevitably generate significant economic, ecological, and urban-design consequences for the surrounding area.

So what’s going on behind the scenes as your Prius awaits your return? You might not like it. Here, a nuts-and-bolts breakdown of the problems with different parking typologies.

Parking garages

Parking garages, multi-level structures usually built in denser urban areas, are designed to house many cars in a relatively compact space. Garages are “very expensive to build,” says Donald Shoup, because of the prime urban real estate, building permits, and building materials they require. Maintenance costs for garages are also high. As such, they are usually built not “because developers think they’ll make money,” but in order to satisfy minimum parking standards that most cities require by law. They also have among the highest vacancy rates of any parking infrastructure. However, because most garages are open-air and compact, they are friendlier to the environment than other urban forms of parking.

Cost per space (annual): $1,265 (suburban), $1,598 (urban), $2,645 (urban, underground)[16]

Average occupancy rate: 50%-75% [17]

Environmental impact: Because they are open-air and high-density, garages are greener than other parking modes. However, they also contribute to urban heat islands and often use a lot of electricity because of lighting-level requirements, during both day and night.

Design issues: The Urbanist writes that according to the conventional wisdom, parking garages should “‘blend in’ or ‘minimize their impacts’ on surrounding urban fabrics. [They are] a necessary evil, far superior to surface parking in terms of both urban form and efficiency” and should be designed “with the lessons of context and human scale still internalized….If we’re going to build housing for cars, let’s first do no harm. Then, strive to make things of beauty.”[18]

On-street parking

“On-street parking uses less land per space than off-street parking,” because it requires no driveway, says Victoria, B.C.-based transportation planner Todd Litman. “But the land it uses often has a high opportunity cost” — precluding other types of infrastructure such as bike paths, traffic lanes, wider sidewalks, and landscaping. In addition, because street parking is often free or low-cost, and limited in quantity, vacancies are usually few. This high occupancy rate and low cost leads drivers to “doggedly search for a free curb space” (rather than pay for a garage space) — a phenomenon known as cruising.

Cost per space (annual): $408 (suburban), $578 (urban)[19]

Average occupancy rate: Highly variable depending on the city. Cities actively managing their parking strive for 85% daytime occupancy; without management, downtown occupancy often reaches 100%. At night, vacancies can be 50% or above.[20]

Environmental Impact: Cruising — the practice of circling the block until a spot opens up — has serious environmental impacts. Because it can add, on average, 10.6 stop-and-go minutes (in New York City)[21] to 11.5 minutes (in Cambridge, Mass., ibid) to the time of each journey, it increases air pollution in cities.

Design issues: Badly managed street parking that leads to cruising also contributes to increased traffic in downtowns. Shoup finds that at any given time in cities around America, between 8 and 74 percent of total cars on the road are simply looking for parking.[22]

Surface lots

“Surface lots are cheap to build,” with the lowest per-space cost of any parking typology, says Eran Ben-Joseph. That made them a popular choice for developers and municipalities during the suburban boom and resulting urban decline of the 1950s through 1970s. Today, sprawling surface parking commonly surrounds malls and office parks, and blocks of downtown real estate are occupied by paved lots. The proliferation of surface lots in and outside cities has had profound environmental and urban-design impacts on the country.

Cost per space (annual): $408 (suburban, shopping area); $780 (urban)[23]

Average occupancy rate: 35% – 45% (suburban, shopping area[24]); urban areas vary widely. One study found that occupancy rates in Iowa City, IA averaged 36%, and only reached 74% during the busiest days of shopping just before Christmas.[25]

Environmental impact:

- Runoff. Impermeable surfaces like pavement increase stormwater volume and speed — a combination known as “runoff” — up to 16 times over a similarly sized meadow. Runoff not only physically reconfigures the shape and velocity of streambeds (bad for fish and vegetation), it also introduces oil, metals, and soils into waterways and prevents the recharge of aquifers (bad for our potable water supply). In large metropolitan areas, unsustainable parking lot design may be responsible for up to 132.8 billion gallons of waste water each year (enough to supply 3.6 million American households).

- Heat island effect. Replacing natural vegetation with parking lots also results in increased temperatures for the surrounding area. Because of its dark color and low moisture content, asphalt captures and retains excessive heat, making lots up to 30 degrees hotter than other surfaces[26]. This “heat island” effect creates higher demand for air conditioning in surrounding buildings, among other impacts.

- Light pollution. Lighting engineers often make parking lots very bright to increase safety at night. However, this “radiating obtrusive light… tends to wash out the darkness low in the sky and trespass on neighboring properties,” writes Ben-Joseph.[27]

Design issues:

- Pensacola Parking Syndrome. Urban surface lots are often blamed for clinching the decline of the American downtown after suburbanization in the 1960s. Writes Ben-Joseph in Rethinking A Lot, “In the mid-twentieth century, downtown central business districts tried to compete with suburban shopping centers by tearing down dilapidated buildings and turning them into parking lots.” As planners tried to entice visitors back downtown, parking lots — hardly an inviting feature — often became the most salient aspect of the inner city. By the 1970s, for example, 74 percent of Detroit’s downtown had been turned over to cars. Even today, nearly one-third of the central business district in Orlando, Fla., is covered in asphalt[28].

- Asphalt seas. In retail areas, developers build parking lots to accommodate the massive crowds expected on the busiest shopping day of the year (Black Friday). As a result, malls and big-box stores are surrounded by acre upon acre of paved land (for a two-story building, 80% of a site must be set aside for surface parking, says Ben-Joseph[29]). This creates a land-use pattern in which individual buildings are surrounded by seas of asphalt, a low-density design that makes pedestrianism nearly impossible and contributes to suburban sprawl.

Safety concerns: Parking lots and garages must be designed to minimize the possibility that pedestrians will be struck by a vehicle; create an environment that deters criminal behavior because perpetrators feel they will be seen; and minimize tripping hazards (snow buildup, ice, oil spots, etc.) through proper maintenance. When these conditions are not met, the owner of a parking facility may be liable.

What some shopping malls in L.A. have begun doing is charging for parking in the malls…after three hours…. Century City is a big one in L.A. First they started charging for the first three hours, and now next year, they’re going to charge everybody.

… The mall parking garages are very well set up for charging for parking if they want to, and I think that if they’re going to charge for parking, they shouldn’t have a uniform price all day, all year. They should have a lower price most of the year, maybe a higher price at that time when you say, ‘Well, I can’t find any spaces.’ Well, the idea of the right prices is you’ll always find a space.

That’s the idea of the right pricing. You’ll always find a space, and nobody will be able to say there’s a shortage of parking because everywhere they go, they’ll see a few spaces, just as there’s no shortage of fur coats or iPads or anything else. The only thing there’s a ‘shortage’ of is parking. There’s no shortage of gasoline or telephones or eyeglasses or Pepsis. The one thing there’s no shortage of that people complain about is parking and that’s because cities have decided that it ought to be free.

– Donald Shoup, on how to solve America’s parking dilemmas, interview with MyParkingSign, Dec. 2012

America may no longer lead the world in car ownership — with just over two people for every car, it is now ranked 25th globally, according to the Carnegie report[30] — but our passion for parking has not diminished along with our love for cars.

Some experts reckon the ratio is more like three to one, and generous estimates range as high as eight to one. “It’s easily possible that every driver has a spot at home, one at work, and one at the mall or other recreational space,” figures Mark Chase, from Nelson/Nygaard

The expectation of plentiful free parking everywhere a driver might go, a relic of the era of suburban expansion of the 1950s-1980s, has led to the paving of America, with acre upon acre of asphalt surrounding suburban office parks and malls. “Since I cannot realistically get from my home to shopping, restaurants — or anywhere else, really — without a car, availability of parking (and the time it will take to park) is always a factor,” says Claire Whittaker, a retired public relations executive who lives just outside Charlottesville, Virginia. That’s why she rarely chooses to shop and eat on the city’s pedestrianized downtown mall, a place where city officials have intentionally limited parking to encourage foot traffic and reduce car traffic. “I have to really want to dine at a particular place to make it worth the trouble.”

Donald Shoup jokes that this attitude, which is common among drivers, is “an example of Stockholm Syndrome” — that is, Americans are sympathetic to their “captors,” the automobile.

Given the understandable lure of parking to drivers, urban planners today are discovering better ways to manage parking than just to “pave paradise and put up a parking lot,” as folksinger Joni Mitchell once cautioned.

One easy response to America’s glut of parking is simple redesign. For example, you can hide parking lots behind buildings rather than putting them out front. “Many communities are now requiring that storefronts be built up against the sidewalk, with parking in the back,” says Chase.

This outcome may also result naturally from infill, the process of developing vacant land within an already built-up area to increase density. Building new street-front retail in front of set-back strip malls, for example, creates a sort of courtyard parking lot surrounded by buildings, decreasing the visibility of parking and fomenting a more walkable environment. Developers can mitigate the negative effects of being in the “back row” of retail by offering shops prominent signage out front, notes Chase.

Another design alternative that actually somewhat reduces the amount of asphalt is space differentiation. In Rethinking a Lot, Ben-Joseph suggests organizing lots to accommodate different types of vehicles , such as motorcycles (several of which could fit in a standard 18-by-9-foot space) and compact cars (which require 20 percent less space than their full-size cousins and grow ever more popular with consumers).

But parking experts like Chase and others say better design isn’t enough. Modern parking practices must begin to reflect changes in the demand for parking due to lower car ownership rates and changes in how Americans get around.

“Parking minimums are regulated by inadequately researched standards mostly set in the 1950s,” says Chase. “Over the years, they’ve gotten worse, as each municipality raises them just a little—because, you know, nobody wanted to have too little parking.” Today, developers routinely overbuild parking and supply exceeds demand by between 35 and 50 percent, depending on the type of development. This practice wastes not just land but money, creating costs that are passed on to consumers.

Chase advises business owners and developers to monitor their actual parking needs, and use that data to override zoning regulations. In The High Cost of Free Parking, Shoup highlights a study commissioned by Home Depot which found that its parking needs corresponded not with store size but with sales. Standard parking minimums based on square footage, it turned out, were requiring it build more than double the number of spaces needed even on its busiest days. Because Home Depot can predict sales quite accurately, it now requests variances that allow it to build lots tailored to each store’s demand.

Such data also suggests another promising, innovative solution: shared parking lots. In this model, nearby buildings with different patterns of parking needs utilize a single lot. For example, offices have highest demand from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., while residential buildings need their spaces from 5 p.m. to 8 a.m., so areas with mixed-use developments can use one lot to serve two different communities of drivers. In the town of Portsmouth, N.H., for example, guests at the Ale House Inn may park overnight in the St. John’s Episcopal Church lot across the street. Such arrangements allow each business to meet its individual parking needs with half the spots.

Its sheer ubiquity makes it difficult to examine nationwide parking trends. Estimates of the number of parking spots vary by tens of millions. There’s so much of it, and it’s spread across such a wide swathe of the country, that even satellite data has proved incomplete and difficult to tally.

Individual communities may require zoning permission for building lots, but they don’t necessarily monitor the total number of off-street, on-street or private lots within their borders, and even if they did, there is currently no national parking clearinghouse or census to collect such data.

Even if it’s hard to pin a number on our national parking stock, we can learn about parking trends indirectly – one way is through signage. Signage may not tell us everything about any single parking typology, but variations in demand for signs and permits does give us a general idea of how the public conceptualizes these spaces, what property owners find expedient and desirable, what kinds of development are occurring.

MyParkingSign.com has access to exactly this data. MyParkingSign.com is an affiliate of SmartSign, an online manufacturer and distributor of signs, tags, mats, and labels. After licensing its design tools to Staples, FedEx, OfficeMax, and Grainger, in 2005, SmartSign began to sell directly to its customers, giving it unprecedented information on parking trends.

Today, SmartSign is one of America’s 500 largest internet firms, serving over one million customers and operating dozens of affiliate sites, including MyParkingSign, MySafetySign, MySecuritySign, and MyParkingPermit. Sales data from previous incarnations reaches back well into the 1990s, giving the company a singular historical perspective on changes to the American parking scene over the past twenty years.

As part of an internal review of market trends, SmartSign and MyParkingSign have uncovered several findings that hint not only at America’s parking past, but what parking experts can expect over the next few years.

Findings

Reserved parking signage

Design variations, 2006: 22

Design variations, 2013: 450+

Total sales of reserved parking signs designating parking spots for compact cars, carpooling, or cars using alternative fuels:

2008: approx. 100 signs

2012: approx. 3000 signs

Summary: When MyParkingSign began, sales of reserved parking were confined to a relatively small number of SKUs (indeed, the most popular said simply, RESERVED PARKING.) Although demand effects are difficult to discern, the market can support sales of a variety of signage several orders of magnitude greater than even in the mid-2000s. Today, MyParkingSign sells signs that say RESERVED FOR PASTOR where before the sign may simply have read RESERVED.

Time-limited signage

Median minutes listed on time-limited parking signage:

2008: 45 minutes

2013: 20 minutes

Sales of time-limited signage, 2009-2012:

1 hour free parking: -26%

5-15 minutes free parking: +52%

Summary: This was one of the central features of sign-buying trends, and one of the most surprising. When we dug into our statistics, we found that when private lot owners limit motorists’ time in their lots, the time allotted has shrunk enormously in recent years. Although it’s difficult to assess a single reason for this trend, based on anecdotal evidence from sales staff, we believe that it’s due to several converging trends: growth in the value-priced restaurant sector and takeout food, growth in the rental market (as opposed to home ownership), and retailers actively seeking out a high volume of low-ticket purchases in a poor economy.

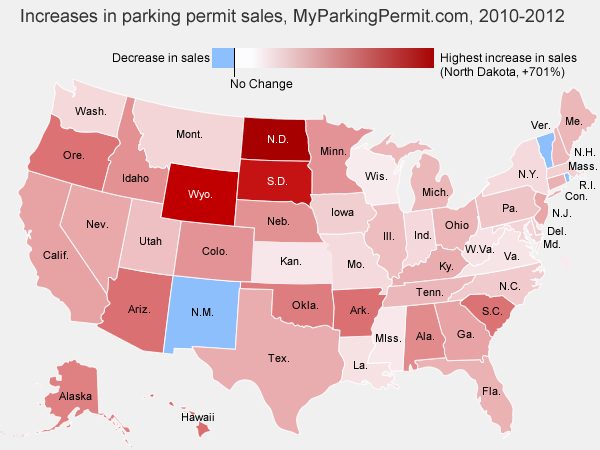

Parking permits

Most popular parking sign, 2009: Stock sign with the text RESERVED PARKING

Most popular parking sign, 2012: PARKING PERMIT REQUIRED

Average order size for the top-selling parking permit decal, 2008: $283

Average order size for the top-selling parking permit decal, 2012: $161 (-43%)

Traffic for search term “parking permits,” 2008-2013: +170%

Summary: The overall growth in parking permits sales – even as order size shrinks – reflects a tendency for smaller and smaller lots to see permit systems as a viable option for monetizing their lots, as well as increased worries about parking lot security. The above map illustrates almost across-the-board growth, with sales of permits skyrocketing in the Dakotas and Wyoming (North Dakota’s marked growth is, we suspect, an indirect result of the Bakken shale oil boom).

Product diversity

Share of sales of top-selling parking-related signs, by year

[raw]

| 1992 | 2002 | 2008 | 2012 | |

| 26% | 12% | 10.00% | 8.80% | Top 10 sign designs |

| 19% | 9% | 6.70% | 6.30% | Top 5 sign designs |

[/raw]

Summary: Twenty years ago, the top 10 designs constituted over a quarter of all parking signs sold by MyParkingSign’s progenitor business; today they make up less than 10% of sales. Some of this can be explained by improvement in the customization options our company offers, but it’s just as significant that the public is willing to take advantage of a diverse parking product base, and sees custom options as desirable.

When we think of our homes, our offices, our stores, we usually imagine them ending at their front doors. This perception is shifting, at a glacial but still noticeable pace – and organization, monetization and careful planning are all becoming as important to the private lot as they are to stocking a store’s shelves.

1. Ben-Joseph, Eran. 2012. ReThinking a lot: the design and culture of parking. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

2. Hobbs, Frank and Nicole Stoops. 2002. U.S. Census Bureau, Census 2000 Special Reports, Series CENSR-4, Demographic Trends in the 20th Century. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

3. (Ben-Joseph 2012)

4. Duany, Andres, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, and Jeff Speck. 2000. Suburban nation: the rise of sprawl and the decline of the American Dream. New York: North Point Press.

5. Dadush, Uri B., and Shimelse Ali. 2012. In search of the global middle class a new index. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://www.carnegieendowment.org/files/middle_class.pdf.

6. (Ben-Joseph 2012)

7. Kalita, Mitra, and Robbie Whelan. “No McMansions for Millennials.” Wall Street Journal, January 13, 2011. Accessed April 04, 2013. https://blogs.wsj.com/developments/2011/01/13/no-mcmansions-for-millennials/.

8. Chozick, Amy. “As Young Lose Interest in Cars, G.M. Turns to MTV for Help.” The New York Times. March 23, 2012. Accessed April 04, 2013. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/23/business/media/to-draw-reluctant-young-buyers-gm-turns-to-mtv.html.

9. (Carnegie 2012)

10. Trudell, Craig, and Alan Ohnsman. “Chevy Sonic-to-Fiat 500 Surge in Big Year for Small Cars.” Bloomberg. October 08, 2012. Accessed April 04, 2013. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-10-08/chevy-sonic-to-fiat-500-surge-in-big-year-for-small-cars.html.

11. Weissman, Jordan. “Why Don’t Young Americans Buy Cars?” The Atlantic. March 25, 2012. Accessed April 04, 2013. https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/03/why-dont-young-americans-buy-cars/255001/.

12. Shoup, Donald C. 2005. The high cost of free parking. Chicago: Planners Press, American Planning Association.

13. Aubin, Kate. “The Hidden Cost of America’s Parking Problem.” Three Ninety Eight (web log), May 21, 2010. Accessed April 04, 2013. https://threeninetyeight.com/2010/05/21/parking-costs/.

14. Murphy, James J. and Mark A. Delucchi . 1997. Review of Some of the Literature on the Social Cost of Motor-Vehicle Use: Report #3 in the series: The Annualized Social Cost of Motor-Vehicle Use in the United States, based on 1990-1991 Data. Davis, CA: Institute of Transportation Studies, University of California, Davis, Research Report UCD-ITS-RR-96-03(03)

15. Litman, Todd. 2006. Parking management best practices. Chicago, lll: American Planning Association.

16. (Litman 2006)

17. Internal sales statistics ParkMe.com [provided during unpublished interview]

18. Grant, Benjamin. “Five Parking Garages – an Urbanist’s Reluctant Crush.” SPUR, May/June 2011. Accessed April 04, 2013. https://www.spur.org/publications/library/article/urban-field-notes-

five-parking-garages-—-urbanists-reluctant-crush.

19. (Litman 2006)

20. (Shoup 2005)

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

23. (Litman 2006)

24. Ibid.

25. Shaw, John. “Minimum Parking Requirements in Midwestern Zoning Ordinances.” Paper presented at 76th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board, January 1997.

26. (Ben-Joseph 2012)

27. Ibid.

28. Tracy, Dan. “Orlando Has Too Many Parking Places, Experts Say.” Orlando Sentinel. August 26, 2012. Accessed April 04, 2013. https://articles.orlandosentinel.com/2012-08-26/news/os-orlando-too-much-parking-20120826_1_rich-unger-downtown-orlando-regional-director.

29. (Ben-Joseph 2012)

30. (Dadush 2012)

31. (Ben-Joseph 2012)

32. Tsaousis, Andrew. “Small Cars Sales on the Rise in the U.S., Could Account for 20 Percent of the Market This Year.” Carscoops, October 9, 2012. Accessed April 04, 2013. https://www.carscoops.com/2012/10/small-cars-sales-on-rise-in-us-could.html.https://www.carscoops.com/2012/10/small-cars-sales-on-rise-in-us-could.html

33. Internal sales statistics, MyParkingSign.com, SmartSign.com, and MyParkingPermit.com. March 2013.

[raw]

[/raw]

Related Posts

Category: Miscellaneous